In all areas of modern working life, whether in business, public administration, or military alliances, there appears to be an agreement that the leadership style of managers not only affects the working behavior and motivation of employees, but also has an indirect impact on the effectiveness and efficiency of the organization as a whole. A large part of international leadership research is concerned with investigating the degree to which leaders involve those they lead in decision-making processes. What is actually being decided on – e.g. operational processes, appointments, or future strategic market orientation – is not important in the first instance. In the German armed forces (Bundeswehr), there are clear regulations concerning the extent of participation in decision-making. The Joint Service Regulation (Zentrale Dienstvorschrift, ZDv) for the management philosophy of the Bundeswehr, called Innere Führung (leadership development and civic education), unmistakably calls upon the military leader: “I lead as a partner. I make use of the skills and abilities of my soldiers and involve them whenever possible in the decision-making process.” (ZDv A-2600/1, p. 27). Some findings from research into leadership styles at a specific type of organization – the multinational military headquarters – are presented and discussed below. In part, they can be transferred to leadership in military organizations in general.

Research into leadership styles

In the academic literature on leadership, the degree of involvement in decision-making processes is often thought of as a continuum from a more directive to more participative leadership style.1 It is assumed that leaders cultivate a particular (individual) leadership style. For a social-science investigation of leadership styles, a four-way typology has proven expedient and has formed the basis for many questionnaire surveys: authoritarian, paternalistic, participative, and democratic leadership styles. If a leader takes decisions quickly, communicates these directly and straightforwardly to their employees, and then expects these instructions to be carried out loyally and without criticism, one speaks of an authoritarian leadership style. If a leader generally takes decisions alone, but attempts to explain the rationale of their decision and responds to questions from their subordinates, then they would be called paternalistic. Participation in decision-making occurs when employees are consulted and the pros and cons are weighed up together before a decision is finally taken by the leader. The democratic leadership style always requires a discussion with the team, in which arguments are exchanged and ultimately the majority opinion is the binding basis for the decision-making. In the fourth management style, the superior plays a role more like that of a moderator.

State of research on multinational military organizations

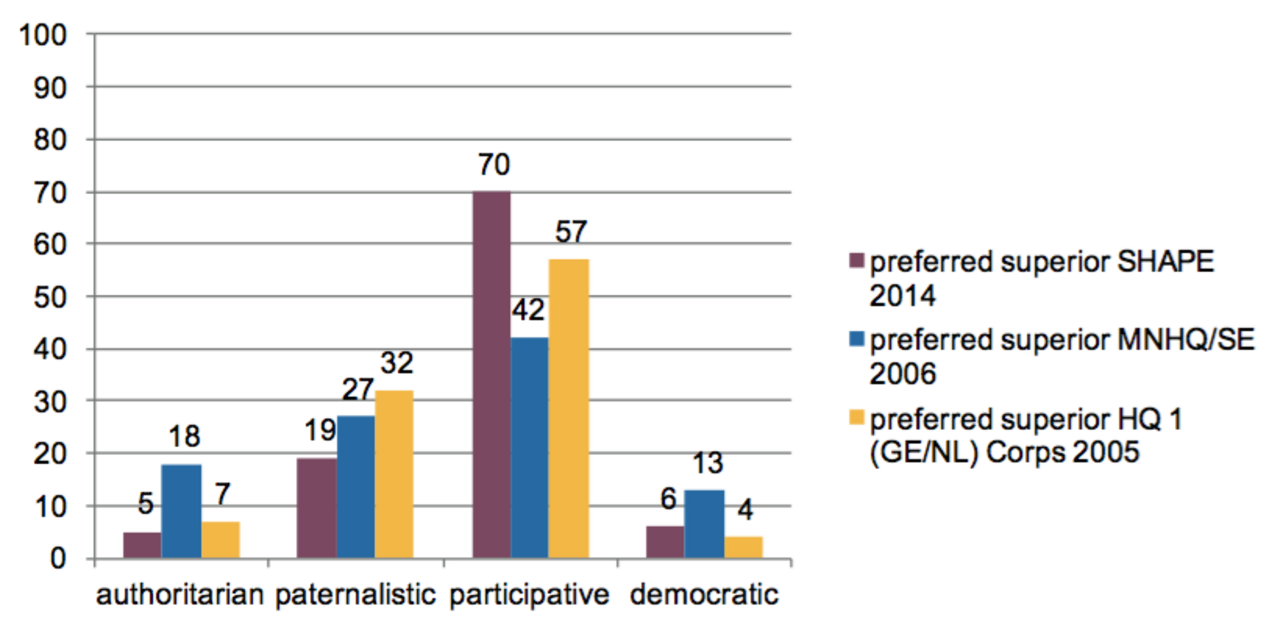

Which of these four leadership styles is preferred by those who are led, and what impact, if any at all, does leadership style have? In recent years, at the former Social Sciences Institute of the German Armed Forces (Sozialwissenschaftliches Institut der Bundeswehr; until 2012) and currently at the German Armed Forces Center for Military History and Social Sciences (Zentrum für Militärgeschichte und Sozialwissenschaften der Bundeswehr, ZMSBw), a number of multinational units and headquarters of NATO and EU missions have been examined. Alongside a range of questions concerning deepened military cooperation2 between the nations involved from the point of view of military and defense policy as well as organizational culture, the researchers have always also taken an interest in the topic of “leadership style.” At three selected headquarters that were studied using the same method (a standardized survey) and identical questionnaire wordings (firstly, SHAPE, the military headquarters of NATO near Mons, Belgium; secondly, MNHQ/SE, the headquarters of the EU ALTHEA mission in Bosnia and Herzegovina: and thirdly, HQ 1 (GE/NL) Corps, the headquarters of the joint German-Dutch corps in Münster), the findings were consistent: staff members at all three headquarters most frequently preferred the participative leadership style (cf. figure 1).

Figure 1: A comparison of preferred leadership styles (sources: Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe 20143, Multinational Headquarters South-East 20064, Headquarters 1st German/Netherlands Corps 2005)5. Figures in percent.

Studies to date have yielded a number of other interesting findings: (i) Patterns of preference for a given leadership style differ between nations – for example, national (military) cultures are apparently reflected in the leadership culture as well; (ii) The preferred leadership style is dependent on the military hierarchy: the higher the rank, the higher the preference for participative and democratic leadership styles; (iii) The leadership style that soldiers observe in their direct superior does not always necessarily match their preferred leadership style. This will be discussed further below; (iv)If one compares the three examples considered in figure 1, it appears that the participative style is preferred mainly in headquarters with a political and strategic orientation (such as is the case with SHAPE), whereas in headquarters such as the ALTHEA mission (i.e. in the theater of operations and in direct proximity to operational military tasks), there are relatively more supporters of the paternalistic and authoritarian leadership styles. To put it in military sociology terms, “cold” organizations carrying out – as it were – basic bureaucratic tasks can allow themselves a higher degree of participation in decision-making, while in “hot” organizations in the vicinity of operational activities and possibly also close to the fighting, there is a greater preference for a conventional model of command and obedience. This fourth statement should be regarded as a provisional finding and, because of its far-reaching implications, should certainly be validated in studies involving other headquarters.

Impact of leadership style?

One concern of the SHAPE study was to close previous research gaps. Previous studies had not focused on the consequences that the observed and desired leadership styles have on the organization’s effectiveness. Even if the participative leadership style appears to those who are led to be the ideal leadership style, is its universal application actually beneficial to the performance of the team and the organization as a whole?

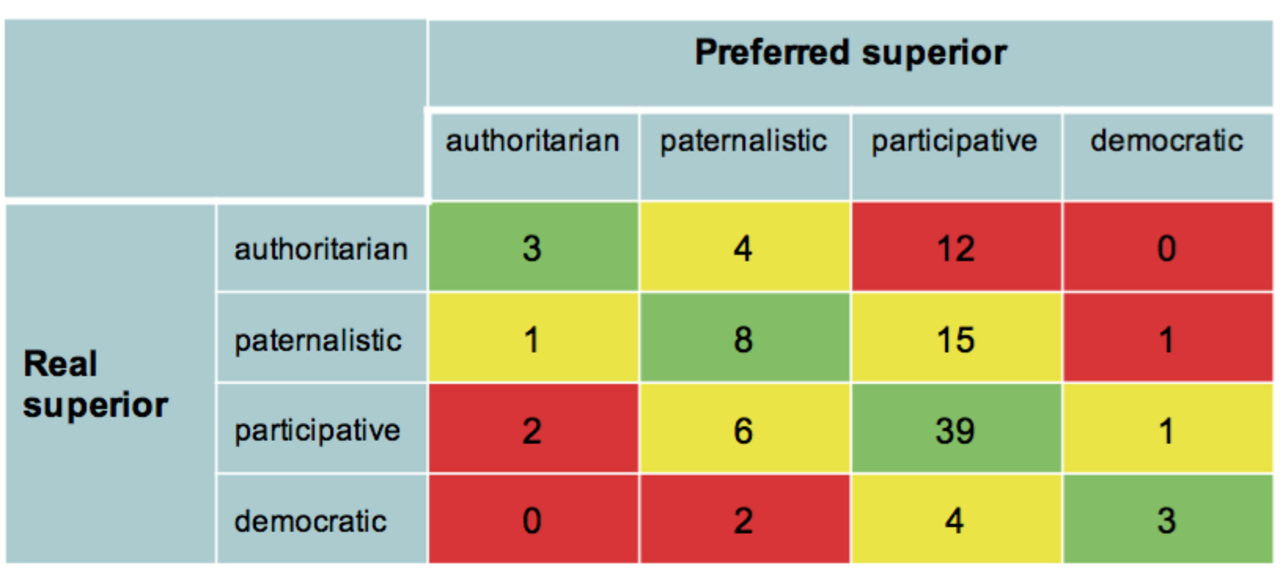

At the time of the survey in the fall of 2014, the multinational staff of SHAPE comprised around 800 mainly military employees from all NATO member countries. The response rate was a pleasing 44 percent. Figure 2 shows that by a narrow majority of 53 percent (green cases), the leadership style that the respondent observed in their direct superior matched their own preferred leadership style. When there is a mismatch at the individual level, a clear preference for more participation can be seen. A not inconsiderable proportion of 27 percent in total, who stated that they were led in a paternalistic (15 percent) or authoritarian (12 percent) way, would prefer a participative style in their direct superior. This concludes the desired/actual comparison.

Figure 2: Comparison of preferred and actual leadership styles (source: own survey at SHAPE, 2014). Congruent cases are shown in green, incongruent cases in yellow and red. Figures in percent.

Further statistical analysis showed, remarkably, that for the assessment in the questionnaire about whether SHAPE is an efficient organization, it makes no difference whether the actual leadership style matches the preferred leadership style. One might have expected that staff members who, for example, have a paternalistic superior, but would like to be led participatively, would rate the performance of SHAPE lower than their colleagues whose wishes corresponded with reality. Yet this was not the case. Similarly, no statistically significant differences in the responses could be found between the 53 percent of congruent cases and the 47 percent of incongruent cases, if one takes mission clarity as the dependent variable, i.e. the extent to which a staff member has a clear understanding of SHAPE’s mission and the organizational goals of the NATO headquarters. Above all, it was astonishing that there is no relationship between leadership style and job satisfaction. In accordance with the state of research in businesses and public organizations, one might have expected that persons who find their ideal boss reflected in their actual boss would show greater satisfaction than their “non-matching” colleagues. This, too, was not the case. To sum up the results in a nutshell: leadership style does not matter!

Conclusion and outlook

The NATO military headquarters is a rather atypical form of organization. It stands at the top of what is currently the largest and most powerful military alliance in the world. Mainly staff officers from the 28 member nations work at the headquarters in a multinational and multicultural context. In accordance with the state of research on other forms of organization, however, it is also true for SHAPE that superiors do not actively involve the employees and soldiers under their command in decision-making processes to the extent which those who are led believe should be the case. Nevertheless, the study indicates that – at least in this specific form of organization – the significance of leadership style, perhaps also the importance of leadership in general, is apparently not as great as one would have assumed for military organizations. In an organizational culture designed around coordination and consensus between 28 nations, such as that of SHAPE, the microrelation of “leader-led,” while it certainly does not retreat entirely into the background, nevertheless apparently plays a rather secondary role in the everyday process of decision-making in and between the departments. But even without demonstrable objective impacts at the organizational level or on the effectiveness of military headquarters, the requirement for a participative leadership culture – as is also formulated in the German armed forces’ Joint Service Regulation on Innere Führung – remains indispensable from the point of view of leadership ethics, and should be put into practice in everyday operational routines, not least in the military.

1 Bass, Bernhard M. (1990): Bass & Stogdill’s Handbook of Leadership. Theory, Research, and Managerial Applications, 3rd ed., New York/London, pp. 436–471.

2 Gareis, Sven Bernhard (2016): “Multinationalität als militärsoziologisches Forschungsgebiet,” in: Dörfler-Dierken, Angelika and Kümmel, Gerhard (eds.): Am Puls der Bundeswehr. Militärsoziologie in Deutschland zwischen Wissenschaft, Politik, Bundeswehr und Gesellschaft, Wiesbaden, pp. 169–188.

3 Biehl, Heiko, Moelker, René, Richter, Gregor, and Soeters, Joe (2015): OCS – Study on SHAPE’s Organizational Culture, April 2015 (unpublished report).

4 Santero, Manuel Casas and Navarro, Eulogio Sánchez (2006): “Leadership in Mission Althea 2006–2007,” in: Leonhard, Nina et al. (eds.): Military Cooperation in Multinational Missions: The Case of EUFOR in Bosnia and Herzegovina (SOWI-Forum International, vol. 28), Strausberg, pp. 161–190.

5 Vom Hagen, Ulrich (2006): “Communitate Valemus – The Relevance of Professional Trust, Collective Drills and Skills, and Task Cohesion within Integrated Multinationality,” in: Vom Hagen, Ulrich, Moelker, René, and Soeters, Joe (eds.): Cultural Interoperability. Ten Years of Research into Cooperation in the First German-Netherlands Corps (SOWI-Forum International, vol. 27), Breda and Strausberg, pp. 53–95.